Hypokalemia Management Calculator

Potassium Replacement Calculator

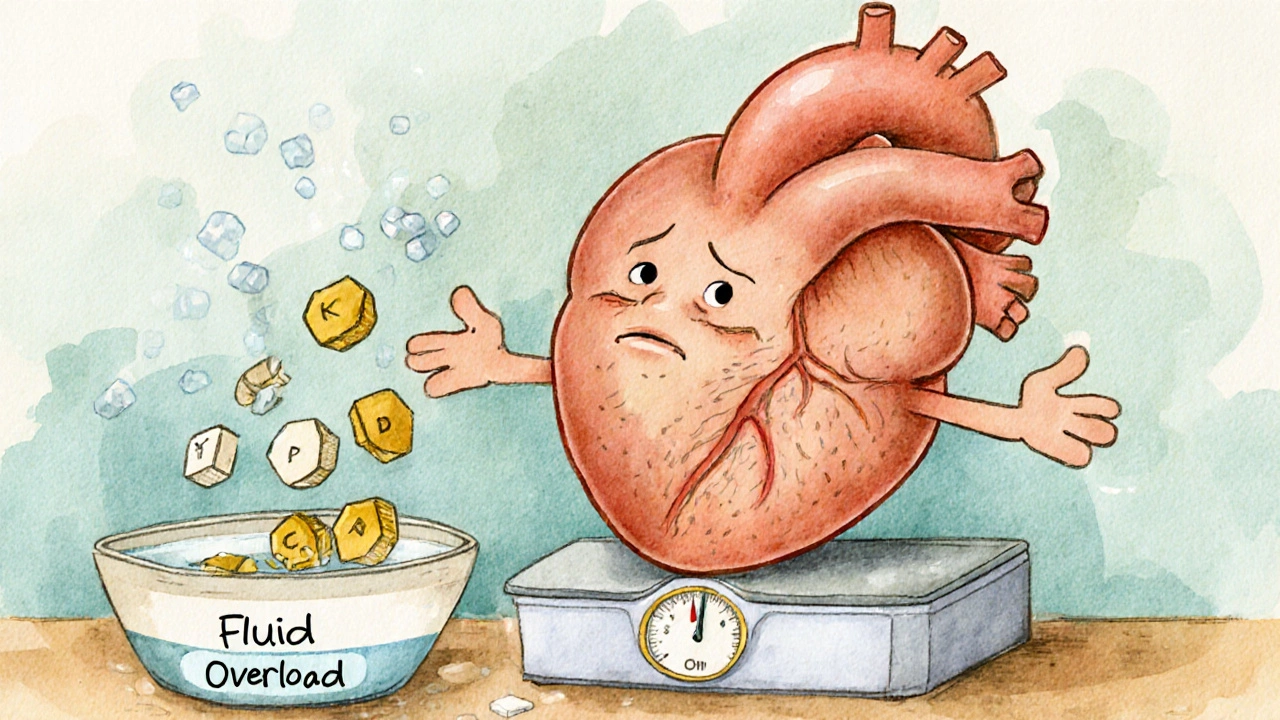

When you have heart failure, your body holds onto too much fluid. That’s why doctors often prescribe diuretics - pills that help you pee out the extra water. But here’s the catch: the same drugs that relieve swelling can also drain away something vital - potassium. Low potassium, or hypokalemia, isn’t just a lab number. In heart failure patients, it can trigger dangerous heart rhythms, raise the risk of sudden death, and make your condition worse.

Why Diuretics Lower Potassium

Loop diuretics like furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide are the go-to for heart failure. They work in the kidneys, blocking salt and water reabsorption. But here’s how they mess with potassium: when salt gets flushed out, it pulls potassium along with it. The more diuretic you take, the more potassium you lose - especially if you’re on high doses or taking them daily without breaks.It’s not just the dose. Timing matters too. Giving a single large dose of furosemide in the morning causes a big spike in potassium loss. But splitting the dose - say, 20 mg in the morning and 20 mg in the afternoon - smooths out the effect. Studies show this reduces the swings in potassium levels, making them easier to manage.

And it’s not just diuretics. If you’re also on other meds like laxatives, steroids, or even some antibiotics, your potassium can drop even faster. Even strict salt restriction - something your doctor tells you to do - can backfire. Less salt means your body releases more aldosterone, a hormone that pushes potassium out through your urine. So, cutting salt too hard can accidentally worsen hypokalemia.

What’s a Safe Potassium Level?

The goal isn’t just to avoid low numbers. It’s to keep potassium between 3.5 and 5.5 mmol/L. Below 3.5 is hypokalemia. Below 3.0 is serious and needs urgent action. At this level, your heart becomes electrically unstable. Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation can happen without warning - especially if you already have heart damage from heart failure.Studies show that heart failure patients with potassium below 3.5 mmol/L have a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of dying. That’s not a small risk. It’s why doctors check potassium levels every week when starting or changing diuretics. Once things stabilize, monthly checks are enough - unless you’re sick, hospitalized, or your dose changes.

How to Fix Low Potassium

If your potassium drops, don’t just reach for a banana. You need a plan.- Mild hypokalemia (3.0-3.5 mmol/L): Take oral potassium chloride. Most patients get 20-40 mmol per day, split into two doses. Avoid potassium supplements with meals - they’re better absorbed on an empty stomach.

- Severe hypokalemia (below 3.0 mmol/L): This needs IV potassium in the hospital. You’ll get 10-20 mmol per hour, with continuous ECG monitoring. Never give IV potassium fast - it can stop your heart.

But here’s the smarter move: don’t just replace potassium. Prevent it from leaving in the first place.

Use Potassium-Sparing Medications

The best way to stop potassium loss isn’t more pills - it’s changing the drug combo. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) like spironolactone and eplerenone block aldosterone. That means less potassium leaks out of your kidneys. These aren’t just potassium savers - they save lives.The RALES trial proved it: adding spironolactone (25 mg daily) to standard heart failure treatment cut death risk by 30% in severe cases. Today, guidelines say every heart failure patient with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) should be on an MRA - unless they can’t tolerate it or have very high potassium.

Start low: 12.5 mg of spironolactone or 25 mg of eplerenone. Check potassium in 3-5 days. If it’s under 5.5, keep going. If it’s above 5.5, hold the dose and recheck.

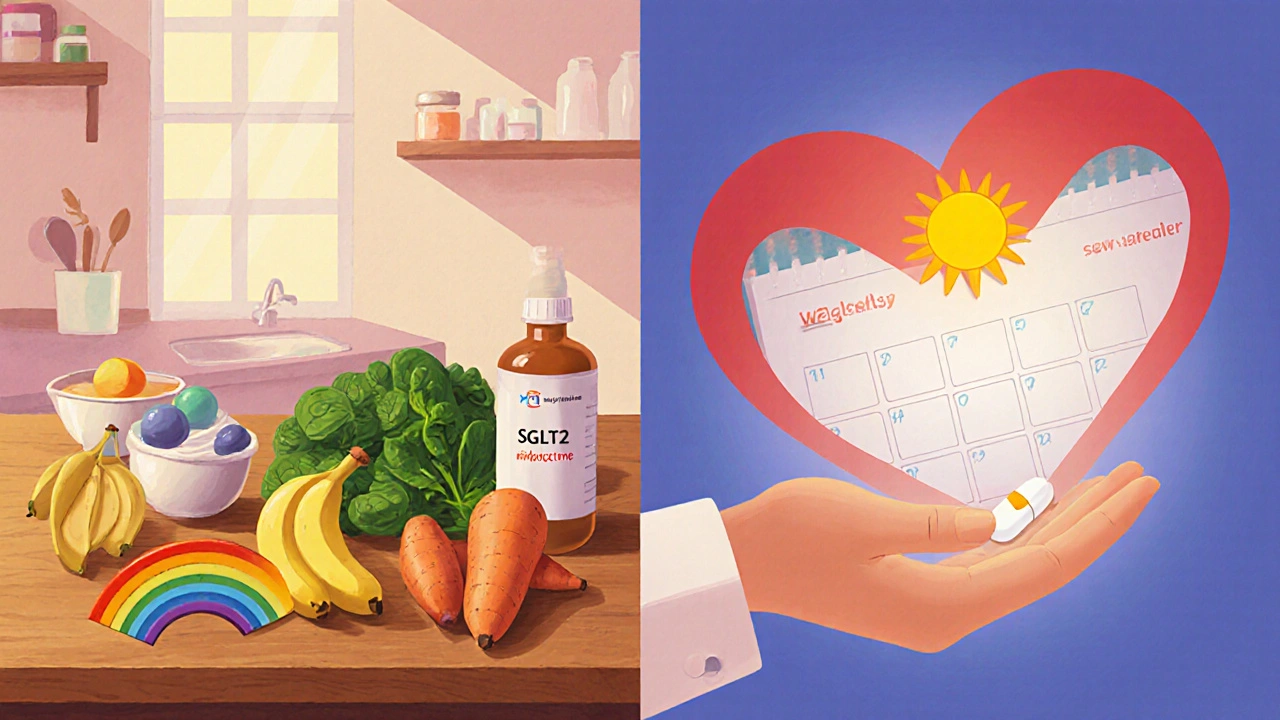

SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Game Changer

In the last five years, a new class of drugs has changed heart failure care: SGLT2 inhibitors. Originally for diabetes, drugs like dapagliflozin and empagliflozin now have a clear role in heart failure - even if you don’t have diabetes.They work by making your kidneys dump sugar and salt. That pulls out extra fluid - so you need less diuretic. Clinical trials show SGLT2 inhibitors reduce diuretic needs by 20-30%. Less diuretic? Less potassium loss.

And unlike diuretics, SGLT2 inhibitors don’t cause hypokalemia. In fact, they often slightly raise potassium levels. That’s why they’re now recommended as a core treatment for both HFrEF and HFpEF. If you’re on high-dose diuretics and keep having low potassium, adding an SGLT2 inhibitor might be the solution.

When to Add a Thiazide

Some patients need more than loop diuretics. They’re resistant - meaning they don’t pee enough even on high doses. The trick? Add a low-dose thiazide like metolazone (2.5-5 mg daily).This combo - loop + thiazide - works like a one-two punch. The loop hits the kidney early; the thiazide hits later. Together, they get rid of more fluid. But here’s the trade-off: thiazides also cause potassium loss. So if you add metolazone, you must also add or increase your MRA or potassium supplement.

Never add a thiazide without a potassium-sparing plan. It’s a recipe for dangerous lows.

What to Watch For

Keep an eye on these red flags:- New muscle weakness or cramps

- Palpitations or skipped heartbeats

- Feeling lightheaded or faint

- Constipation (low potassium slows gut movement)

If you notice any of these, call your doctor. Don’t wait for your next appointment. A simple blood test can catch a problem before it becomes life-threatening.

Also, check your meds. Are you taking a laxative? An OTC supplement? A new antibiotic? These can all tip the scales. Bring your full list to every visit - even the stuff you think doesn’t matter.

Don’t Forget Diet

Bananas aren’t the only source of potassium. Sweet potatoes, spinach, beans, avocados, oranges, and yogurt are all good. Aim for 3-4 servings of potassium-rich foods daily. But don’t overdo it. If you’re on an MRA or have kidney disease, too much potassium can be just as dangerous as too little.Work with a dietitian. They can help you balance fluid, salt, and potassium without leaving you hungry or tired. And remember: no magic foods. It’s about consistent, daily choices.

What’s Next?

The future of managing hypokalemia in heart failure is personal. Doctors are starting to use biomarkers - like BNP levels and kidney function - to tailor diuretic doses. One study showed that using this approach reduced hypokalemia by 15-20% compared to standard care.Extended-release diuretics are also in development. These release the drug slowly, avoiding the big spikes that cause potassium crashes. And new potassium binders - mostly used for high potassium - might one day help fine-tune levels in both directions.

For now, the best strategy is simple: use the least diuretic needed, add an MRA, consider an SGLT2 inhibitor, monitor potassium often, and eat smart. It’s not about avoiding diuretics - it’s about using them wisely.

Can I just take a potassium supplement instead of changing my meds?

Oral potassium supplements can help with mild lows, but they’re not a long-term fix. If you keep losing potassium, it means your treatment plan needs adjustment - not just more pills. Adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (like spironolactone) or an SGLT2 inhibitor tackles the root cause. Supplements can cause stomach upset and don’t prevent the heart rhythm risks that come with ongoing low potassium.

Is hypokalemia more dangerous in heart failure than in healthy people?

Yes. In healthy people, low potassium might cause mild cramps. In heart failure patients, the heart is already weakened and scarred. Low potassium makes the heart’s electrical system unstable, increasing the risk of sudden cardiac arrest. Studies show heart failure patients with potassium below 3.5 mmol/L have up to twice the risk of death compared to those with normal levels.

Why can’t I just stop taking my diuretic if my potassium is low?

Stopping diuretics can cause fluid to build up again - leading to worsening shortness of breath, swelling, and hospitalization. The goal isn’t to stop the drug, but to manage the side effect. That’s why we use potassium-sparing agents, adjust doses, or add SGLT2 inhibitors. These let you keep the benefits of diuretics without the dangerous drop in potassium.

Do all diuretics cause hypokalemia?

No. Loop diuretics (furosemide, bumetanide) and thiazides (hydrochlorothiazide) cause the most potassium loss. But potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone, eplerenone, and amiloride do the opposite - they help keep potassium in. That’s why they’re often used together: to balance out the effects.

How often should I get my potassium checked?

When you start or change your diuretic dose, check potassium every week for the first month. Once stable, monthly checks are usually enough. But if you get sick, start a new medicine, or feel symptoms like weakness or palpitations, get tested right away. More frequent checks are needed during hospital stays or after a heart failure flare-up.

Can I use salt substitutes if I have low potassium?

Be careful. Many salt substitutes are made with potassium chloride. If you’re already taking potassium supplements or an MRA, using these can push your potassium too high - which is dangerous too. Always check with your doctor before using salt substitutes. They’re not a safe shortcut.

Managing diuretics and potassium in heart failure isn’t about perfection. It’s about balance. You need to control fluid without risking your heart’s rhythm. The right mix of medications, careful monitoring, and smart lifestyle choices makes all the difference.

9 Comments

Holli Yancey

I’ve been on furosemide for years and honestly, I never realized how much potassium I was losing until I started getting muscle cramps at night. Switching to split doses made a huge difference-no more midnight leg spasms. Also, I started eating more spinach and sweet potatoes, not just bananas. It’s not magic, but it helps.

And yeah, the MRA thing? My cardiologist put me on spironolactone last year and I haven’t had a single potassium check below 4.0 since. Life-changing.

Gordon Mcdonough

STOP TELLING PEOPLE TO EAT BANANAS!!! That’s like telling someone with diabetes to eat candy because it has sugar!!! This is MEDICINE not a grocery list!!! You want potassium?? Take the damn pill!!! Why are we letting people think food fixes everything??

And who the hell says ‘split doses’ like it’s a yoga routine?? It’s a medical protocol not a TikTok hack!!!

Jessica Healey

omg i literally just had a potassium panic last week and this post saved me. i was taking furosemide 40mg every morning and my legs were cramping so bad i couldn’t walk. my dr didn’t even check my k+ for 3 weeks. i was terrified. then i read about splitting the dose and adding spironolactone and now i’m on 20mg am + 20mg pm + 12.5mg spiro. no more cramps. no more panic. thank you.

also, i started eating yogurt with my breakfast and it’s weirdly satisfying. who knew dairy could be a lifesaver?

Levi Hobbs

Great breakdown. I’d just add that many patients don’t realize that OTC laxatives-especially those with senna or bisacodyl-can be major potassium thieves. I had a patient who was taking laxatives daily for ‘regularity’ and his potassium kept crashing despite supplements. Once we stopped the laxatives and added eplerenone, everything stabilized.

Also, don’t forget that some antibiotics like amphotericin B and gentamicin can worsen this too. Always review the full med list-not just the heart meds.

henry mariono

Thanks for sharing this. I’ve been managing HF for 8 years and this is the clearest summary I’ve seen. I especially appreciate the note about salt restriction increasing aldosterone. That’s counterintuitive but makes total sense. I’ve been cutting salt too hard and didn’t realize I was making things worse.

Just wish more doctors explained this to patients instead of just saying ‘take your pills’.

Sridhar Suvarna

As a doctor from India, I see this daily. In resource-limited settings, many patients can’t afford MRAs or SGLT2 inhibitors. We use low-dose spironolactone whenever possible and teach patients to eat coconut water, lentils, and bananas. It’s not perfect, but it saves lives.

Also, in our clinics, we check potassium every 5 days when starting diuretics-not every week. We don’t have luxury of waiting. Practicality over protocol sometimes.

Joseph Peel

One thing missing from this otherwise excellent overview is the role of magnesium. Hypomagnesemia often coexists with hypokalemia and makes potassium replacement less effective. Many clinicians overlook it. If potassium won’t stay up, check magnesium. Supplement if below 1.8 mg/dL. Simple, cheap, and often overlooked.

Kelsey Robertson

Oh wow. So we’re supposed to believe that SGLT2 inhibitors are some kind of miracle drug now? Really? The same ones that caused Fournier’s gangrene in some patients? And you’re telling people to just ‘add one’ like it’s a new flavor of yogurt?

And don’t get me started on MRAs-spironolactone gives men boobs and makes them moody. Is that the trade-off we’re willing to make? Maybe we should just let people die quietly instead of poisoning them with hormones and sugar-drainers.

Also, who wrote this? It reads like a pharma ad disguised as medical advice.

Joseph Townsend

Bro. This isn’t just medicine. This is a war. A silent, electrolyte-based war inside your own body. Diuretics are the enemy generals, and potassium is the last soldier holding the hill. You don’t just throw more soldiers at the problem-you restructure the whole damn army.

MRAs? That’s your special forces. SGLT2 inhibitors? That’s the drone strike from above. And splitting doses? That’s the guerrilla tactic-small, steady, no big explosions.

And yeah, I’ve seen people go from ‘I can’t breathe’ to ‘I’m walking my dog again’ with this combo. It’s not just science. It’s redemption.