When someone is struggling with depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, doctors often turn to medication to help stabilize their mood, thoughts, and behavior. But what happens when one pill isn’t enough? In many cases, clinicians add another. And then another. This isn’t rare-it’s becoming the norm. In the UK alone, nearly 1 in 4 adults with serious mental illness are taking three or more psychiatric drugs at once. This is called psychiatric polypharmacy, and while it sometimes helps, it often creates more problems than it solves.

Why Do Doctors Prescribe So Many Medications?

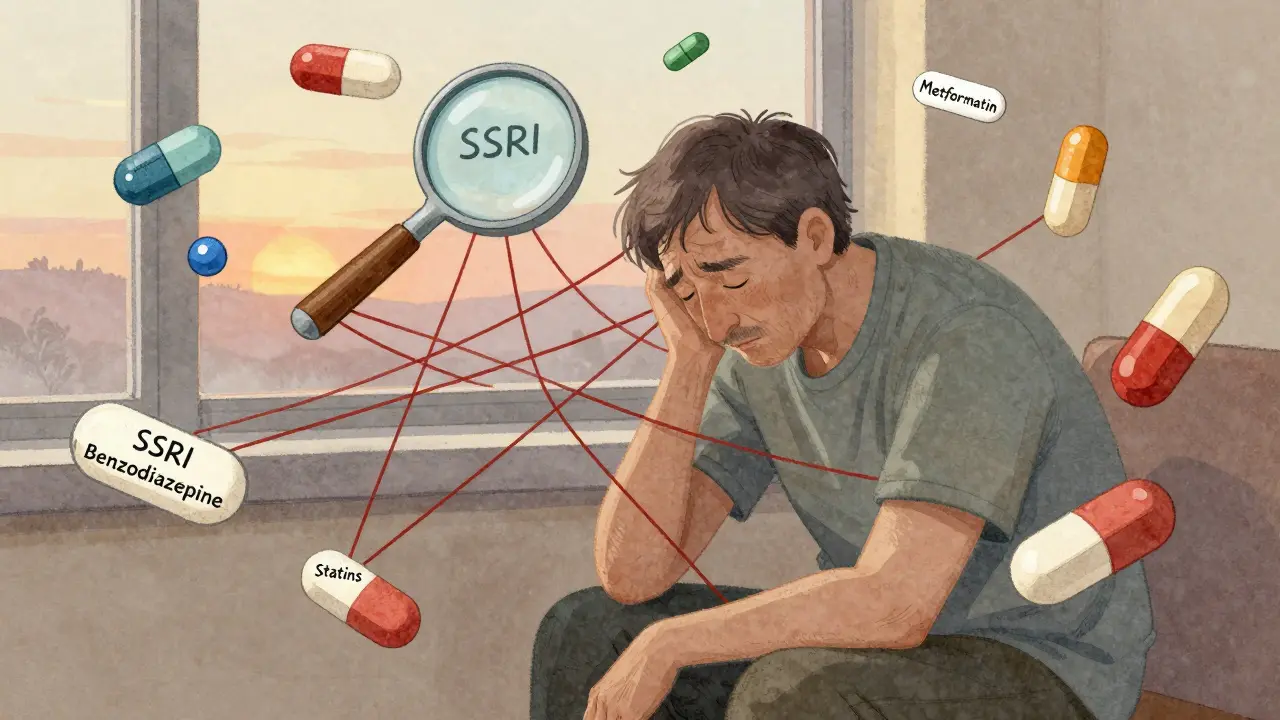

It starts with good intentions. A patient takes an antidepressant, but their anxiety doesn’t improve. So a benzodiazepine is added. Then their sleep stays broken, so a sedating antipsychotic is thrown in. Maybe they gain weight, so metformin is prescribed. Then their cholesterol spikes-statin added. Before long, a person is on six or seven medications, none of which were meant to be taken together long-term.

The reality? Many of these combinations aren’t backed by solid science. A 2012 study in JAMA Psychiatry found that antipsychotic polypharmacy-using two or more antipsychotics at once-jumped from 3.3% to 13.7% among Medicaid patients with schizophrenia between 1999 and 2005. But the evidence for this practice? Almost none. Most guidelines say it should only be used after all other options fail. Yet in practice, it’s often the first move.

Some combinations do work. Adding bupropion to an SSRI like citalopram can help people who don’t respond fully to antidepressants alone. Using a mood stabilizer like lithium with an antipsychotic can control acute mania. Short-term use of benzodiazepines with antidepressants can ease severe anxiety during early treatment. But these are exceptions. Most polypharmacy regimens are built on trial and error, not evidence.

The Hidden Risks: When More Isn’t Better

Every additional medication increases the chance of side effects-and dangerous interactions. Antidepressants like SSRIs can raise serotonin levels. Add an opioid like tramadol, or even St. John’s Wort, and you risk serotonin syndrome: a life-threatening spike in body temperature, confusion, rapid heartbeat, and muscle rigidity.

Antipsychotics, especially older ones like haloperidol, can cause tremors, stiffness, and tardive dyskinesia-a condition where people develop uncontrollable facial movements. When combined with other drugs that affect dopamine-like anti-nausea meds or certain antibiotics-the risk skyrockets.

Older adults are especially vulnerable. As liver and kidney function slow with age, drugs build up in the body. A 70-year-old with schizophrenia might be on an antipsychotic, an antidepressant, a blood pressure pill, a statin, and a painkiller. Each one competes for the same enzymes to be broken down. The result? Toxic levels, dizziness, falls, confusion. A 2023 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology showed that older patients with schizophrenia are now taking more non-psychiatric drugs than psychiatric ones-drugs meant for heart disease, diabetes, arthritis. These aren’t treating their mental illness. They’re treating the side effects of their mental illness meds.

And the impact isn’t just physical. A CDC study found that people taking five or more medications daily reported significantly lower quality of life-less energy, more pain, worse mobility-regardless of their mental health diagnosis. Their depression scores didn’t get worse, but their ability to live well did.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Anyone with a chronic mental illness is vulnerable. But certain groups face higher risks:

- Older adults: Their bodies process drugs slower. They’re more likely to be on multiple meds for physical conditions, creating a perfect storm for interactions.

- People in primary care: Nearly 40% of patients receiving mental health treatment in general practice settings are on complex polypharmacy regimens. These doctors aren’t psychiatrists. They’re managing 20 patients an hour. They don’t have time to untangle drug interactions.

- People with multiple physical illnesses: If you have diabetes, heart disease, and depression, you’re statistically more likely to be on five or more drugs. This isn’t coincidence-it’s the norm.

- Those on long-term medication: Someone on an antidepressant for 10 years may have had three different drugs added over time, each for a different symptom. No one ever stepped back to ask: “Do we still need all of these?”

When Polypharmacy Makes Sense

Not all polypharmacy is bad. Sometimes, it’s necessary. But it should be intentional, not accidental.

For example:

- A person with treatment-resistant depression who hasn’t responded to two different antidepressants might benefit from adding a low-dose antipsychotic like aripiprazole-this is FDA-approved and supported by trials.

- Someone with bipolar disorder in a manic phase might need lithium plus an antipsychotic to bring symptoms under control quickly.

- A patient with psychosis and severe anxiety might need an antipsychotic plus a short-term benzodiazepine until the main drug kicks in.

In these cases, the combination has been studied. The doses are low. The goal is clear: stabilize, then taper. But too often, the taper never happens. The extra meds become permanent fixtures.

How to Cut the Clutter-Safely

Reducing medications isn’t about taking away help. It’s about removing noise so the real treatments can work.

A 2024 study tracked 120 patients over 18 months as their psychiatric regimens were carefully reviewed. The average number of drugs dropped from 4.8 to 2.9. Side effects like weight gain, drowsiness, and tremors fell by over 60%. Blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar improved too. Mood scores stayed stable-or got better.

How? Three steps:

- Map every pill: List every medication-prescribed, over-the-counter, herbal. Include doses and why it was started.

- Ask the hard questions: Is this drug still needed? Was it meant to be temporary? Is it helping, or just adding risk?

- Taper slowly: Never stop cold turkey. Reduce one drug at a time, over weeks or months. Watch for return of symptoms. If nothing changes, it was probably unnecessary.

Patients often fear that reducing meds will make them worse. That’s valid. But staying on five drugs you don’t need? That’s a slow decline. One woman, 68, was on seven medications-including an antipsychotic she’d been taking for 15 years after a single psychotic episode in her 40s. When it was slowly withdrawn, her balance improved. Her memory cleared. She stopped falling. Her depression didn’t return.

The Tools That Are Changing the Game

There’s new hope on the horizon.

Pharmacogenomic testing looks at your genes to see how your body breaks down certain drugs. Some people metabolize SSRIs too fast-so the drug doesn’t work. Others process antipsychotics too slowly-so they get side effects at low doses. Testing can cut trial-and-error by 30-50%, according to the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology in 2022. It’s not perfect, but it’s a step toward precision.

Some clinics now use treatment algorithms-step-by-step decision trees-to guide prescribing. In one Early Psychosis Intervention Programme in the UK, doctors reduced antipsychotic polypharmacy by 80% just by following a clear protocol. No more guessing. No more adding meds because “it couldn’t hurt.”

And deprescribing-systematically removing unnecessary drugs-is gaining traction. By 2025, over 60% of academic medical centers plan to have formal deprescribing programs. But right now, 78% of clinics still don’t have a standard way to do it.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you care about is on multiple psychiatric medications:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this still necessary?”

- Request a full medication review-every 6 to 12 months.

- Bring a list of everything you take, including supplements and OTC pills.

- Don’t be afraid to ask: “What happens if we stop this one?”

- Find a psychiatrist or pharmacist who specializes in psychopharmacology. They’re trained to untangle these webs.

Medication isn’t the enemy. But blind polypharmacy? That’s a silent crisis. Too many people are drowning in pills-not because they need them, but because no one took the time to ask if they still worked.

The goal isn’t fewer drugs. It’s better ones. Fewer side effects. More life.

Is it safe to take multiple psychiatric medications at once?

It can be, but only when carefully planned. Some combinations, like adding a low-dose antipsychotic to an antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression, are supported by research. But many others-especially using two antipsychotics together-are not. The risk of dangerous interactions, side effects, and long-term harm increases with each added drug. Always ask why each medication is being prescribed and whether it’s truly necessary.

Can psychiatric polypharmacy make depression worse?

Yes. While medications are meant to help, too many can cause fatigue, brain fog, weight gain, and metabolic issues-all of which can deepen feelings of hopelessness. Some drugs interact in ways that reduce the effectiveness of others. For example, certain antibiotics or antifungals can block how SSRIs work, making depression feel worse even if you’re taking them as prescribed.

What are the most dangerous drug interactions in mental health treatment?

The most dangerous include serotonin syndrome (from combining SSRIs with tramadol, MDMA, or St. John’s Wort), neuroleptic malignant syndrome (from antipsychotics with lithium or SSRIs), and QT prolongation (from mixing certain antipsychotics with antibiotics or heart meds). These can be fatal. Always check for interactions with a pharmacist before starting or stopping any medication.

Why do doctors keep adding more medications instead of stopping ones?

It’s easier. Adding a drug takes minutes. Removing one requires careful planning, monitoring, and follow-up. Many doctors lack time, training, or confidence to taper safely. Patients often fear relapse, so they don’t push back. There’s also a cultural belief that “more is better.” But evidence shows that simplifying regimens often leads to better outcomes-with fewer side effects and higher quality of life.

Can pharmacogenomic testing help reduce polypharmacy?

Yes. Testing can show how your body processes specific drugs-whether you’re a fast or slow metabolizer. This helps avoid prescribing drugs that won’t work or will cause side effects. Studies show it can reduce adverse reactions by 30-50% in psychiatric patients. While not a magic solution, it cuts down trial-and-error, making it easier to find the right dose with fewer pills.

How can I start reducing my medications safely?

Never stop cold turkey. Start by making a full list of every medication, supplement, and herb you take. Bring it to your doctor or a psychiatric pharmacist. Ask: “Which of these are essential? Which were meant to be temporary?” Work with your provider to taper one drug at a time, over weeks or months. Track your mood, sleep, and side effects. If symptoms return, it may mean you still need it. If nothing changes, you might be able to stop safely.

10 Comments

LOUIS YOUANES

This is exactly why I stopped trusting psychiatrists. They treat symptoms like a grocery list instead of seeing the person. I was on 7 meds for 5 years. My brain felt like a broken radio. One day I just stopped. Not cold turkey, but slow. Now I meditate, lift weights, and drink too much green tea. I’m not ‘cured’-but I’m alive.

Pawan Kumar

The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has weaponized diagnostic ambiguity. Polypharmacy is not clinical practice-it is corporate strategy disguised as care. The FDA’s approval process is a revolving door. Clinical trials are funded by the very companies profiting from multi-drug regimens. This is systemic exploitation masquerading as science.

Keith Oliver

Bro. I had a doc throw an antipsychotic at me because I cried during a therapy session. That was 2019. I’m still on it. No one ever asked if I needed it. My weight’s up 40 lbs, I’m always sleepy, and my girlfriend left. But hey, my ‘mood stability’ is ‘on target.’ This system is broken. And everyone’s too tired to fix it.

Kacey Yates

I work in a psych clinic and I see this daily. Patients on 6+ meds because no one had the time to wean them. Doctors are overworked. Pharmacies don’t flag interactions. Patients are scared to ask. We need more pharmacist-led deprescribing. It works. I’ve seen it. Stop adding. Start removing. One at a time. No drama. Just science

ryan Sifontes

they just keep adding pills because its easier than admitting they dont know what theyre doing

Laura Arnal

I was skeptical at first but my sister cut from 5 meds to 2 over 8 months. Her energy came back. She started painting again. She cried when she realized she hadn’t slept through the night in 12 years. This isn’t about quitting meds-it’s about finding your real self under all the chemical fog. You deserve that. 💛

Jasneet Minhas

Ah yes, the great American psychiatric buffet. More pills = more progress. In India, we call this ‘kitchen sink therapy.’ But here? It’s called ‘standard of care.’ Funny how the same logic that would get you fired in engineering is celebrated in medicine.

Eli In

I’m from a rural town. My mom’s on 8 meds. She’s 72. She can’t walk without a cane. She forgets her own name sometimes. But her ‘depression is managed.’ I showed her this article. She said, ‘I just want to feel like me again.’ That’s all. Not more pills. Just… her. We’re failing people like her every day.

Robin Keith

The ontological weight of psychiatric polypharmacy cannot be overstated. We are not merely treating biochemical imbalances-we are enmeshing the subject in a labyrinth of pharmacological signifiers, where the self becomes a site of pharmaceutical negotiation. Each pill, a metaphysical gesture; each interaction, a rupture in the phenomenological integrity of lived experience. The medical gaze, in its hubris, has forgotten that the mind is not a machine to be calibrated-but a horizon to be honored. And yet, we prescribe. And prescribe. And prescribe.

Doug Gray

The evidence base for polypharmacy is statistically negligible. The risk-benefit calculus is skewed by publication bias, industry influence, and the inertia of clinical habit. We’ve normalized iatrogenic harm as collateral damage. The term ‘treatment-resistant’ is often just a euphemism for ‘we ran out of ideas.’ Deprescribing isn’t radical-it’s restorative. And yet, the system resists. Because convenience > competence.