Over 80% of people diagnosed with multiple myeloma will develop severe bone damage. It’s not just a side effect - it’s a core part of the disease. These aren’t ordinary fractures or wear-and-tear injuries. They’re osteolytic lesions - holes in the bone that look like they’ve been punched out on an X-ray. And they don’t just hurt. They break bones without warning, crush spines, spike calcium levels, and send patients to the hospital. For years, treatment focused only on slowing the damage. Now, a new wave of drugs is trying to reverse it.

How Myeloma Turns Bone Into Swiss Cheese

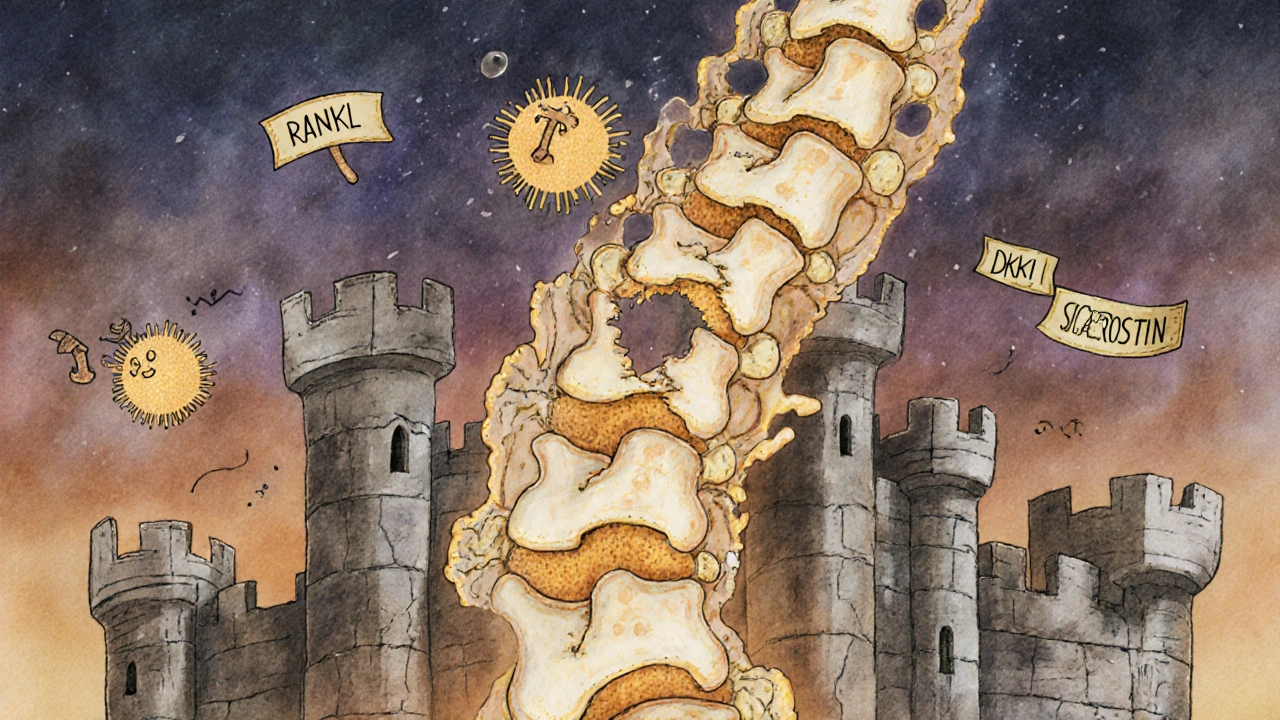

Your bones aren’t static. Every day, old bone is broken down by cells called osteoclasts, and new bone is built by osteoblasts. In healthy people, these two processes balance each other. In multiple myeloma, that balance shatters. Myeloma cells move into the bone marrow and send out chemical signals that flip the system into overdrive. Osteoclasts go wild, chewing through bone. Osteoblasts shut down. No new bone is made. The result? Holes that keep growing.

The key players? A trio of molecules: RANKL, OPG, and DKK1. Myeloma cells crank up RANKL, which tells osteoclasts to eat more bone. At the same time, they suppress OPG - the natural brake on RANKL. That ratio shifts by 3 to 5 times in patients compared to healthy people. Then there’s DKK1, a protein secreted by myeloma cells that blocks the Wnt pathway - the body’s main signal for building bone. Patients with DKK1 levels above 48.3 pmol/L have over three times more bone damage than those with lower levels. Even osteocytes, the most common bone cells, get pulled into the chaos. They release sclerostin, another bone-building blocker, averaging 28.7 pmol/L in myeloma patients versus 19.3 in healthy individuals.

This isn’t just a one-way street. As bone breaks down, it releases growth factors trapped in the bone matrix - things like IGF-1 and TGF-beta - that feed the myeloma cells. So the more the bone is destroyed, the more the cancer grows. And the more the cancer grows, the more bone it destroys. It’s a cycle. And it’s why treating the cancer alone doesn’t fix the bones.

What Happens When Bones Break Down

The consequences aren’t abstract. They’re lived. One in three patients will suffer a pathological fracture - a break that happens because the bone is too weak, not because of trauma. Spinal cord compression affects 5 to 10%, causing sudden numbness, weakness, or even paralysis. Hypercalcemia - too much calcium in the blood - hits 25 to 30% of patients. It causes confusion, nausea, extreme thirst, and kidney failure. These are called skeletal-related events, or SREs. And they account for about 70% of the disability caused by myeloma.

Patients don’t just suffer physically. The pain is constant and deep. A 2023 Reddit thread with 147 comments from myeloma patients found that 68% still had bone pain despite being on standard bone drugs. Many reported needing strong opioids just to sleep. Others had to undergo emergency dental surgery because of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw - a rare but serious side effect of bone drugs that causes jawbone death. One patient wrote: “I had to have three teeth pulled because my jaw started crumbling. I never thought my bones would turn against me like this.”

Current Treatments: Slowing the Damage

For decades, the only tools were bisphosphonates - drugs like zoledronic acid and pamidronate. Given monthly through an IV, they stick to bone surfaces and kill osteoclasts. They work. They reduce SREs by 15 to 18% compared to placebo. But they don’t rebuild bone. They just slow the destruction. And they come with costs: kidney damage, low calcium, and the dreaded osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Then came denosumab. Approved in 2010, it’s a monoclonal antibody that directly blocks RANKL. It’s given as a monthly shot under the skin. In a 2021 Mayo Clinic study, 74% of patients preferred it over IV bisphosphonates because it was easier, faster, and didn’t require a clinic visit. But it’s expensive - around $1,800 per dose, compared to $150 for generic zoledronic acid. In the U.S., 78% of patients get denosumab. In Europe, it’s only 42% because of cost restrictions. In Asia, bisphosphonates still dominate at 89% usage.

Guidelines from the International Myeloma Working Group now recommend starting one of these drugs as soon as myeloma is diagnosed. A baseline scan - either a full-body low-dose CT or PET-CT - is required to map out existing bone damage. Monthly treatment continues during active therapy. But even with these drugs, many patients still develop new lesions. And no one has seen bone healing. Just less damage.

The New Wave: Drugs That Might Heal Bone

Now, researchers are testing drugs that don’t just stop bone loss - they try to rebuild it. These are the novel agents.

Anti-sclerostin antibodies like romosozumab and blosozumab are the most advanced. Sclerostin is the brake on bone formation. Block it, and osteoblasts wake up. In the 2021 STRUCTURE trial, 49 myeloma patients on romosozumab saw a 53% increase in bone mineral density in the spine after 12 months. Pain scores dropped by 35%. The phase III BONE-HEAL trial, now enrolling 450 patients, is testing whether this translates to fewer fractures and longer survival.

Anti-DKK1 therapies like DKN-01 target the other major blocker of bone growth. In a 2020 trial with 32 patients, DKN-01 reduced bone resorption markers by 38%. It’s not just about bone - it may also slow tumor growth by disrupting the cancer’s environment.

Gamma-secretase inhibitors like nirogacestat block the Notch pathway, which myeloma cells hijack to boost RANKL. In lab models, they cut osteolytic lesions by 62%. Human trials are just beginning, but early signs are promising.

There are setbacks, too. Odanacatib, a cathepsin K inhibitor that reduced bone breakdown by 31%, was pulled from development in 2016 after raising stroke risk. That’s a warning: targeting bone is powerful, but it’s not without danger. Anti-sclerostin drugs can cause low calcium - 12.3% of trial patients needed calcium supplements. Gamma-secretase inhibitors cause severe rashes in nearly 7 out of 10 patients.

Who Gets These New Drugs - And When?

Right now, these novel agents are only available in clinical trials. But that’s changing fast. The FDA approved a new low-dose version of zoledronic acid in April 2023 to reduce kidney risk. The European Hematology Association updated its guidelines in June 2023 to stress early intervention - before fractures happen.

Experts agree: the future isn’t just about choosing between bisphosphonates and denosumab. It’s about combining them with bone-building drugs. Dr. Irene Ghobrial from Harvard says targeting both the tumor and the bone environment is essential. Dr. Brian Durie of the International Myeloma Foundation predicts we’ll be healing bone lesions - not just preventing them - by 2030.

But there’s a catch. Not all patients respond the same. Some have aggressive bone disease. Others barely show any. We still don’t have reliable biomarkers to tell who will benefit most from a new drug. That’s why trials now include detailed bone turnover markers - blood tests that measure how fast bone is breaking down or building up - to personalize treatment.

What This Means for Patients Today

If you have multiple myeloma, here’s what you need to do now:

- Get a full-body bone scan at diagnosis - don’t wait for pain.

- Start a bone-modifying agent immediately - either denosumab or a bisphosphonate.

- Check your kidney function and calcium levels monthly.

- See a dentist before starting treatment and get regular checkups - MRONJ risk is real.

- Ask your doctor about clinical trials for romosozumab, DKN-01, or other novel agents.

- Track your pain levels. If you’re still hurting on current therapy, it’s not normal. Push for a scan or a second opinion.

Support tools like the Myeloma Beacon’s Bone Health Toolkit and the International Myeloma Foundation’s Bone Disease Guide are free, downloadable, and updated yearly. Over 42,000 patients have used them since 2021.

The Road Ahead

The global market for myeloma bone drugs hit $2.8 billion in 2022 and is expected to nearly double by 2028. But money isn’t the real measure. The real measure is how many patients stop breaking bones. How many stop being hospitalized. How many stop living in pain.

For the first time, we’re not just managing bone disease - we’re trying to fix it. The science is clear: the bone isn’t just a victim. It’s a partner in the disease. And now, we’re learning how to turn it back into an ally.

Can multiple myeloma bone damage be reversed?

Currently, standard drugs like bisphosphonates and denosumab can stop further bone loss, but they don’t rebuild bone. New experimental drugs - like romosozumab and DKN-01 - are showing promise in clinical trials for actually increasing bone density and healing lesions. In one trial, patients saw a 53% increase in spinal bone density after 12 months. Full reversal isn’t yet standard, but it’s becoming a realistic goal.

Why do myeloma patients get bone pain even after treatment?

Standard bone drugs reduce the rate of destruction but don’t eliminate it completely. Myeloma cells continue to produce signals that activate bone-eating cells. In addition, existing damage - like fractures or compressed nerves - doesn’t heal on its own. Studies show 68% of patients still report bone pain despite being on treatment. Newer agents targeting DKK1 and sclerostin may help by promoting bone repair, but they’re still in trials.

Is denosumab better than zoledronic acid for bone disease?

Both reduce skeletal-related events by similar amounts. Denosumab is given as a monthly shot, while zoledronic acid requires a 15-minute IV infusion. Many patients prefer denosumab for convenience. It also carries less risk of kidney damage. But it’s much more expensive - about $1,800 per dose versus $150 for generic zoledronic acid. Insurance coverage varies. In the U.S., denosumab is used more often; in Europe and Asia, bisphosphonates are still first-line due to cost.

What are the biggest risks of bone drugs for myeloma?

The main risks are osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), kidney damage, and low calcium. MRONJ affects 5-10% of long-term users and can require dental surgery. Zoledronic acid can harm kidneys, especially in older patients or those with pre-existing kidney issues - about 22% need dose adjustments. Denosumab and newer agents like romosozumab can cause severe hypocalcemia, requiring daily calcium and vitamin D supplements. Gamma-secretase inhibitors cause rashes in over two-thirds of patients.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for a novel bone drug?

You may be eligible if you have active bone disease (new or growing lesions on scans), are on standard therapy but still experiencing pain or new fractures, or have high levels of bone turnover markers like CTX or PINP. Your oncologist can order blood tests and imaging to assess your bone health profile. Most novel agents are still only available through clinical trials. Ask your care team if any trials are open at your hospital or a nearby cancer center.

8 Comments

Joy Aniekwe

So let me get this straight - we’re spending billions to fix bones that are basically Swiss cheese made by cancer, and the best we’ve got is a drug that stops the cheese from getting *more* holes? Meanwhile, patients are still crying in pain because their spine is a popcorn kernel waiting to pop. Bravo, medicine. You’ve turned osteology into a very expensive game of whack-a-mole.

Latika Gupta

I had a cousin with this. She got denosumab and her jaw started dying. They had to pull five teeth. She said the worst part wasn’t the pain - it was the silence. No one talks about how your own body becomes the enemy. I just wanted someone to say it out loud.

Mary Kate Powers

For anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed - you’re not alone. The fact that you’re even looking into this means you’re already fighting harder than most. The new drugs like romosozumab? They’re not magic, but they’re real hope. I’ve seen patients go from wheelchair to walking again after joining trials. Ask your doctor about clinical trials. You deserve to not just survive - you deserve to heal.

Sara Shumaker

It’s fascinating how the body’s architecture is so deeply entangled with disease. Bones aren’t just scaffolding - they’re communication hubs, memory banks of minerals, signaling centers. Myeloma doesn’t just attack cells - it hijacks an entire ecosystem. We’ve spent centuries treating cancer like a rogue soldier, but what if it’s more like a corrupted algorithm rewriting the rules of the whole system? Maybe healing bone isn’t just about drugs - it’s about restoring balance. And maybe, just maybe, that’s the real cure we’re chasing.

jamie sigler

Wow. So after 10 pages of jargon, the takeaway is: ‘Take your shot, hope for the best, and maybe try a trial if you’re rich.’ Thanks for the update, doc.

Bernie Terrien

Let’s cut the fluff: bisphosphonates are the dinosaur of bone care. Denosumab? Fancy, expensive, still just a bandage. But romosozumab? That’s the goddamn phoenix. 53% spine density gain? That’s not treatment - that’s resurrection. The real tragedy isn’t the cancer. It’s that we’re still treating bone like a side note instead of the battlefield.

Peter Lubem Ause

As a former nurse in Lagos, I’ve seen patients with myeloma walk into clinics with broken ribs and no X-ray machine. We used to pray they’d live long enough to get a scan. Now, we have drugs that can rebuild bone - but only if you live in a country with insurance, a specialist, and a pharmacy that doesn’t run out of meds. This isn’t just science. It’s justice. We need these therapies in Africa, not just in Boston. My brother died because he couldn’t get zoledronic acid. Don’t let his death be the cost of progress.

linda wood

Someone mentioned jaw death. I’m that person. I had three teeth pulled. My dentist cried. My oncologist said, ‘We didn’t know it would happen to you.’ But here’s the thing - I’m still alive. And I’m still here. And I’m signing up for the DKN-01 trial next month. If you’re hurting, don’t accept ‘normal.’ Push. Ask. Fight. We’re not just patients. We’re pioneers.