When your lungs can’t expand fully, even simple tasks like walking to the mailbox or tying your shoes become exhausting. That’s often the first sign of pleural effusion-a buildup of fluid between the layers of tissue surrounding your lungs. It’s not a disease itself, but a symptom of something deeper. And if left unchecked, it can lead to serious complications. The good news? We know exactly how to find it, treat it, and stop it from coming back.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

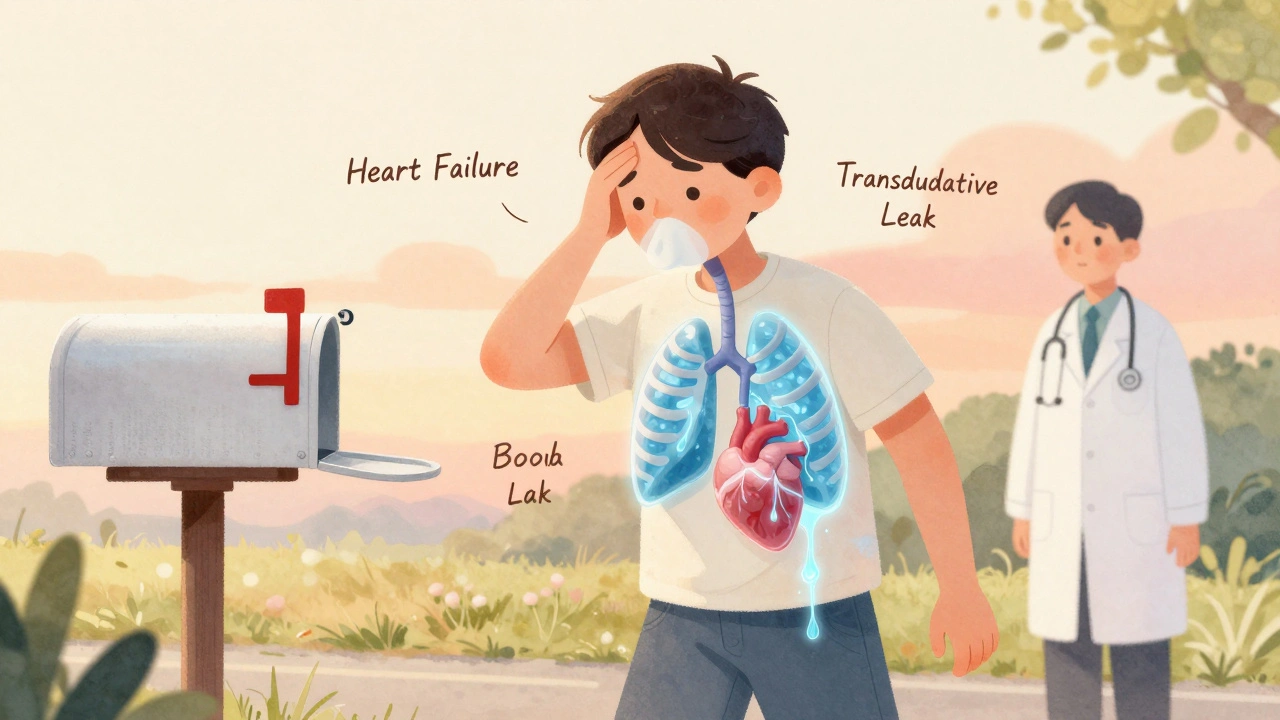

Pleural effusion happens when fluid leaks into the space between your lungs and chest wall. This space is normally filled with just a tiny bit of lubricating fluid. Too much, and your lungs can’t do their job. The cause falls into one of two categories: transudative or exudative.Transudative effusions are like a slow leak from pressure changes. The most common culprit? Congestive heart failure. In fact, about half of all transudative cases come from this. When your heart can’t pump well, fluid backs up into the lungs and surrounding tissues. Liver cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome are other big players here. These conditions mess with protein levels in your blood, making fluid escape more easily.

Exudative effusions are more aggressive. They happen when something inflames or damages the pleural lining. Pneumonia is the top cause, responsible for 40-50% of these cases. Cancer is next-about a third of exudative effusions are linked to tumors, especially lung, breast, or lymphoma. Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung) and tuberculosis also show up often. These aren’t just fluid leaks-they’re signs your body is fighting something serious.

Here’s the key: you can’t tell the difference just by looking. That’s why doctors rely on Light’s criteria, developed in 1972 and still the gold standard today. If your pleural fluid has a protein-to-blood ratio over 0.5, an LDH ratio over 0.6, or LDH levels higher than two-thirds of the normal blood value-it’s exudative. This simple test separates treatable conditions from manageable ones.

When Thoracentesis Is Needed

If you’re short of breath and imaging shows fluid larger than 10mm, thoracentesis is the next step. It’s a simple procedure: a needle or thin tube is inserted between your ribs to drain the fluid. Done right, it gives immediate relief. Done wrong, it can cause serious problems.Ultrasound guidance is now mandatory. Before ultrasound became standard, complications like pneumothorax (collapsed lung) happened in nearly 19% of cases. Now? That number is under 5%. The difference isn’t just safety-it’s accuracy. You’re not guessing where the fluid is. You’re seeing it in real time.

The procedure usually happens in the 5th to 7th rib space along the mid-axillary line. For diagnosis, doctors take 50-100 mL. For symptom relief, they can safely remove up to 1,500 mL in one session. But there’s a catch: removing too much too fast can trigger re-expansion pulmonary edema-a rare but dangerous swelling in the lung after sudden expansion. That’s why doctors monitor pressure during drainage. Keeping it under 15 cm H₂O reduces this risk by 95%.

What they test in that fluid tells the real story. Protein and LDH levels confirm if it’s transudative or exudative. Cell count shows infection (white cells) or cancer (abnormal cells). pH below 7.2? That’s a red flag for complicated pneumonia. Glucose under 60 mg/dL? Could mean empyema or rheumatoid arthritis. LDH over 1,000 IU/L? Often points to cancer. Cytology finds cancer cells in about 60% of malignant cases-but sometimes you need more than one sample.

How to Stop It From Coming Back

Draining fluid helps you breathe better today. But if you don’t fix the root cause, it’ll come back. And it often does.For malignant effusions, recurrence within 30 days after simple drainage is around 50%. That’s why doctors don’t stop at thoracentesis. For patients with cancer and trapped lung, indwelling pleural catheters are now the first choice. These small tubes stay in place for weeks, letting you drain fluid at home. Success rates hit 85-90% at six months. Compare that to talc pleurodesis-where chemicals are injected to stick the lung to the chest wall-which works in 70-90% of cases but often causes intense pain and requires a hospital stay.

Heart failure-related effusions? The fix isn’t surgery. It’s meds. Optimizing diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and beta-blockers cuts recurrence from 40% down to under 15% in three months. Monitoring NT-pro-BNP levels helps doctors adjust treatment before fluid builds up again. It’s not about removing fluid-it’s about fixing the pump.

Parapneumonic effusions (from pneumonia) follow a timeline. Stage one: simple fluid. Stage two: thick, infected fluid with low pH and glucose. Stage three: scar tissue forms. If you wait until stage two or three, you risk empyema-a pus-filled pocket that can kill. Drainage is needed if pH is below 7.2, glucose under 40 mg/dL, or if bacteria show up in the fluid. Antibiotics alone won’t cut it. You need to get the fluid out.

After heart surgery, effusions are common-15-20% of patients get them. Most clear up on their own. But if you’re draining more than 500 mL a day for three days straight, you need a chest tube left in longer. Done right, recurrence drops to just 5%.

What Doctors Are Doing Differently Now

The biggest shift in the last five years? Stopping the overuse of thoracentesis. A 2019 study found that 30% of procedures were done on small, asymptomatic effusions-no benefit, no relief, just risk. Today, guidelines say: don’t drain unless you’re going to treat the cause.For non-malignant effusions, chemical pleurodesis is no longer recommended. There’s no proof it helps. But for malignant ones? Indwelling catheters are now preferred over talc. Why? Patients go home faster-average stay drops from 7 days to 2.1 days. They manage their own drainage. They keep their dignity. And survival? Five-year survival for malignant effusion patients has doubled since 2010, thanks to better cancer treatments and smarter fluid management.

Ultrasound isn’t just a tool anymore-it’s the standard. Dr. Paula Ferraiuolo at Yale says it plainly: “It’s not optional.” Complications drop by 80%. Competency comes after about 25 procedures. That’s why hospitals now train residents with simulators before ever touching a patient.

What You Should Know

If you’ve been told you have pleural effusion, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either. The fluid is a symptom-not the enemy. The real fight is against heart failure, cancer, pneumonia, or another condition hiding beneath it.Ask your doctor: Is this transudative or exudative? What’s the cause? Are we draining just to relieve symptoms, or to prepare for long-term treatment? And if it’s cancer, ask about indwelling catheters. They’re not a last resort-they’re the smartest option for most people.

And if you’re the one getting the procedure? Make sure ultrasound is used. Ask about pressure monitoring. Know that you can manage your care at home with the right tools. This isn’t just about removing fluid. It’s about reclaiming your life.

What is pleural effusion?

Pleural effusion is the abnormal buildup of fluid between the layers of tissue (pleura) that surround the lungs. This fluid restricts lung expansion, leading to shortness of breath, cough, or chest pain. It’s not a disease itself but a sign of an underlying condition like heart failure, pneumonia, or cancer.

How do doctors tell if it’s transudative or exudative?

They use Light’s criteria, based on fluid analysis. If the pleural fluid protein-to-serum protein ratio is over 0.5, the LDH ratio is over 0.6, or the pleural LDH is more than two-thirds of the upper limit of normal serum LDH, it’s classified as exudative. These thresholds help identify inflammatory or malignant causes versus pressure-related leaks like heart failure.

Is thoracentesis safe?

When done with ultrasound guidance, thoracentesis is very safe. Complication rates drop from nearly 19% to under 5%. The most common risks are pneumothorax (collapsed lung), bleeding, or re-expansion pulmonary edema-but these are rare with proper technique. Always ask if ultrasound will be used.

Can pleural effusion come back after drainage?

Yes, especially if the underlying cause isn’t treated. Malignant effusions recur in about 50% of cases after simple drainage. Heart failure-related effusions return in 40% without proper medication. Long-term prevention requires addressing the root cause-whether that’s cancer treatment, diuretics for heart failure, or antibiotics for infection.

What’s the best way to prevent recurrence in cancer patients?

For malignant pleural effusion, indwelling pleural catheters are now the preferred option. They allow patients to drain fluid at home, reduce hospital stays, and have a 85-90% success rate in preventing recurrence at six months. Talc pleurodesis works too but is more painful and requires hospitalization. Catheters offer better quality of life and are recommended by major guidelines.

Do I need to be hospitalized for pleural effusion treatment?

Not always. Simple drainage for symptom relief can be done as an outpatient. For cancer patients, indwelling catheters are inserted once and managed at home. Only complicated cases-like empyema or large effusions needing urgent drainage-require hospitalization. Most people can return to normal activities quickly if the cause is properly managed.

What tests are done on pleural fluid?

Standard tests include protein, LDH, cell count, pH, glucose, and cytology. Additional tests like amylase (for pancreatitis), hematocrit (to detect blood in fluid), and culture (for infection) may be ordered based on symptoms. These help pinpoint the cause-whether it’s infection, cancer, heart failure, or another condition.

Can pleural effusion be cured?

It depends on the cause. Effusions from heart failure can be fully resolved with proper medication. Those from pneumonia often clear with antibiotics and drainage. Malignant effusions can’t be cured, but they can be controlled long-term with catheters or pleurodesis. The goal isn’t always elimination-it’s managing symptoms and improving quality of life.

What Comes Next?

If you’re dealing with pleural effusion, your next steps depend on the diagnosis. Get a full fluid analysis. Confirm the cause. Don’t accept drainage as the end of treatment. Ask about indwelling catheters if cancer is involved. If it’s heart failure, make sure your meds are optimized. Track your symptoms. If breathlessness returns, don’t wait-see your doctor. Early intervention saves lives.The best outcomes come when treatment matches the cause. Not the fluid. Not the symptoms. The disease behind it.

13 Comments

Donna Anderson

this is so helpful!! i had effusion last year and no one explained it like this

thank you for breaking it down like a real person

Lawrence Armstrong

I've seen too many docs just drain and send people home. The real win is using ultrasound + knowing when to stop. 80% fewer complications? That's not magic, that's science. 👍

Stacy Foster

they don't want you to know this but talc pleurodesis is a scam. Big Pharma pushes it because catheters don't make them enough cash. Look at the data - catheters are cheaper, safer, and patients live longer. They're hiding this from you.

Reshma Sinha

The diagnostic algorithm for exudative vs transudative effusions remains anchored in Light's criteria, which maintains high specificity (>90%) despite newer biomarkers emerging. However, the integration of pleural fluid biomarkers such as procalcitonin and mesothelin may enhance predictive accuracy in complex cases.

nikki yamashita

this gave me hope. my mom had it and we thought it was over. turns out there's a way to live with it.

Adam Everitt

i think the real issue is that doctors still dont trust patients to manage their own care... catheters are perfect but they want control... maybe im just paranoid lol

Ashley Skipp

why do they even bother with thoracentesis if its just gonna come back

Nathan Fatal

It’s not about removing fluid. It’s about listening to what the fluid is telling you. Every protein ratio, every pH drop, every abnormal cell - it’s a whisper from your body saying, ‘Something’s wrong here.’ The real medicine isn’t in the needle. It’s in the question: What’s causing this? And then having the patience to answer it.

Robert Webb

I've worked in pulmonology for over 15 years and I can tell you the shift toward indwelling catheters has been one of the most meaningful changes I've seen. It's not just clinical - it's human. Patients who used to feel like burdens in the hospital are now managing their own care at home, watching their numbers, talking to their families. That dignity? That's the real treatment. I've had patients cry when they realized they didn't have to be stuck in a bed anymore just because they had fluid. This isn't just medicine. It's freedom.

sandeep sanigarapu

Good summary. Always treat cause. Not fluid.

wendy b

Honestly if you're not using light's criteria you're just guessing. I mean come on. This is basic. Any med student knows this. And the ultrasound thing? Obvious. Why are we even talking about this?

Rob Purvis

I just want to say - thank you - for mentioning NT-proBNP monitoring. So many clinicians overlook this. It’s not just about diuretics - it’s about tracking the biomarker trend. When NT-proBNP drops below 800 pg/mL in CHF patients, recurrence plummets. And it’s non-invasive! Why isn’t this standard in every primary care office? It should be. Seriously.

Levi Cooper

I work at a VA hospital. We don't use catheters here. We use talc. Why? Because the government says so. The VA doesn't pay for home catheter care. So patients suffer. This isn't medicine. It's bureaucracy. And you know what? They don't care if you live or die - they care about the budget.