Most people think a drug patent lasts 20 years - and that’s technically true. But if you’re waiting for a brand-name drug to drop in price because the patent ran out, you might be waiting much longer than expected. The real story isn’t about a simple countdown. It’s about legal twists, regulatory delays, and corporate strategies that stretch protection far beyond the 20-year mark - or sometimes cut it short. Understanding when a drug patent actually expires isn’t just for lawyers or pharma execs. It affects your prescriptions, your copays, and whether you get access to affordable medicine at all.

The 20-Year Rule Isn’t What It Seems

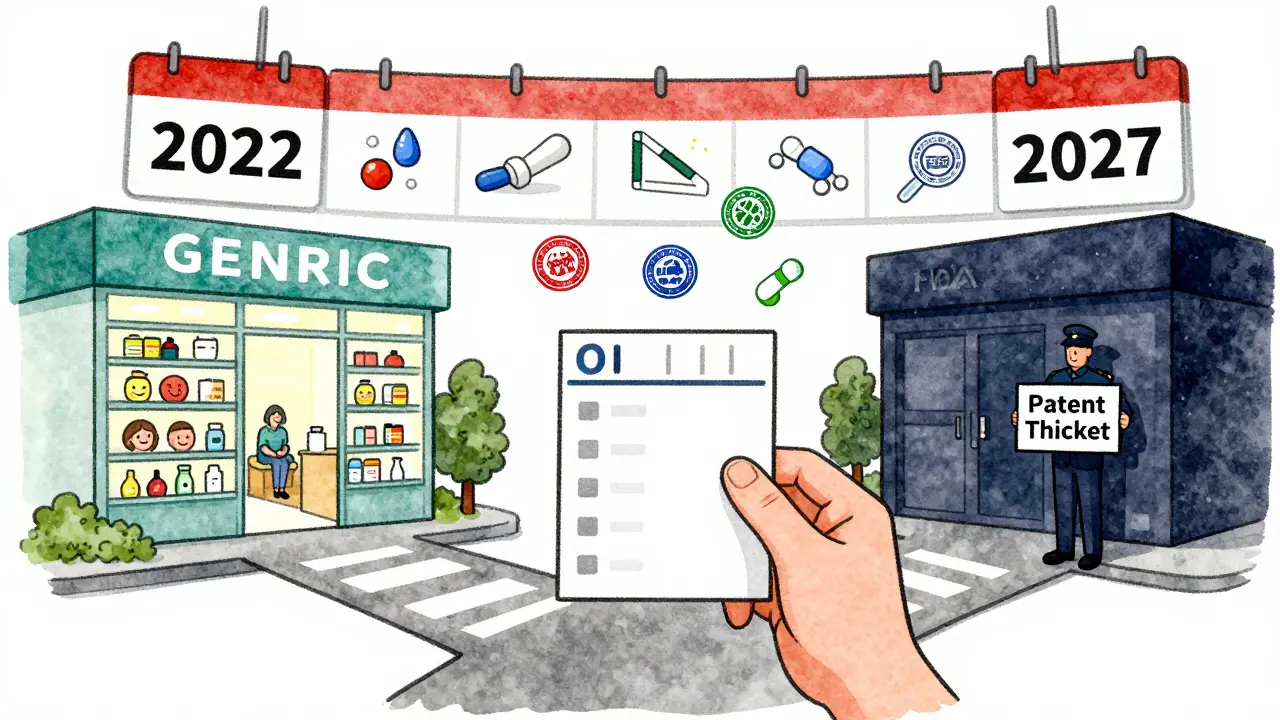

The U.S. patent system gives inventors 20 years of protection from the day they file the patent application. That’s the law. But for drugs, that clock starts ticking long before the medicine even reaches the pharmacy. Most drugs take 8 to 12 years to go from lab to FDA approval. That means by the time a drug hits the market, it’s already halfway through its patent life. A drug filed in 2010 might not get approved until 2020 - leaving only 10 years to make back the $2 billion it cost to develop. That’s why the 20-year term feels misleading. It’s not a 20-year monopoly on sales. It’s a 20-year race against time, with the first few laps spent in clinical trials.How the Patent Clock Gets Extended

To fix this, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984. It lets drugmakers apply for Patent Term Extension (PTE) to make up for time lost during FDA review. The rule? Up to five extra years can be added - but only if the total market exclusivity doesn’t go beyond 14 years after FDA approval. So if a drug gets approved in 2025, the latest it can stay protected is 2039, no matter how long the original patent was. This isn’t automatic. Companies must file for extension within 60 days of approval. Miss that window? You lose it. And it’s not rare. Over 60% of new drugs get some form of extension.More Than One Patent? Welcome to Patent Thickets

A single drug doesn’t have just one patent. It usually has five, ten, or even more. There’s the active ingredient patent - the big one. But then there are patents on the pill’s coating, the way it’s made, how it’s taken, even the packaging. These are called secondary patents. They’re not always groundbreaking, but they’re legally valid. Companies use them to build what experts call a “patent thicket.” When the main patent expires, these others still block generics. Take Spinraza, a rare disease drug. Its core patent expired in 2023, but other patents on delivery methods and dosing schedules keep generics out until 2030. This isn’t fraud - it’s legal strategy. And it’s why you might still pay $100,000 a year for a drug that’s been on the market for 15 years.Regulatory Exclusivity: The Secret Shield

Even without patents, drugs get protection from the FDA. This is called regulatory exclusivity. It’s separate from patents and doesn’t depend on court battles. There are several types:- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years of exclusivity. The FDA can’t even look at a generic application during this time.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 patients in the U.S.).

- New Clinical Investigation: 3 years if the drug gets a new use or dosage that needs new studies.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 extra months if the company studies the drug in children.

These can stack. A drug might have a patent that expires in 2027, but if it got orphan status and pediatric exclusivity, it’s protected until 2034. The FDA’s Orange Book lists all these protections - but it’s not easy to read. Most patients never see this layer.

The Patent Cliff: When Prices Crash

The moment a drug’s last patent and exclusivity expire, it’s called the “patent cliff.” That’s when generic versions flood the market. The drop in price is dramatic. For small-molecule drugs, prices often fall 60% to 80% in the first year. Take Eliquis, the blood thinner. When its patent expired in late 2022, generics captured 35% of the market in six months. By year two, they held over 90%. The brand-name version dropped from $500 a pill to under $50. But it’s not always smooth. Sometimes, insurance companies switch you to a generic - but keep your copay high. One patient reported their copay jumped from $50 to $200 during a 6-month pediatric exclusivity extension. That’s not a glitch. It’s how insurers negotiate.What About Biosimilars?

Biologic drugs - like Humira, Enbrel, or Humalog - are made from living cells, not chemicals. They’re more complex. So their generics, called biosimilars, take longer to develop and get approved. Even after patents expire, biosimilars often take 2 to 3 years to gain traction. Market share? Usually 40% to 60% after five years. Why? Doctors are cautious. Pharmacists can’t automatically swap them in like chemical generics. And the cost to produce them is still high. That’s why Humira, despite losing patent protection in 2023, still had over $15 billion in sales in 2024 - mostly from its biosimilar competitors.How Companies Delay the Inevitable

Drugmakers don’t wait for patents to expire. They plan years ahead. Around Phase II clinical trials - seven years before approval - they start building patent portfolios. They file for new formulations, new delivery systems (like patches or inhalers), or combo pills with other drugs. AstraZeneca’s Tagrisso, a lung cancer drug, saw its main patent expire in 2026. But it now sells a combo version with another drug, protected until 2033. This isn’t cheating. It’s business. The FTC calls some of these moves “evergreening” - filing weak patents just to delay generics. In 2021, the FTC found these tactics can delay generic entry by 2 to 3 years on average.

What’s Changing Now?

In early 2024, Congress introduced a bill called the “Restoring the America Invents Act.” If it passes, it could eliminate some patent term adjustments, cutting protection by 6 to 9 months. The USPTO is also rolling out automated systems to speed up patent reviews - which could reduce extensions. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization is pushing for global patent terms to drop from 20 to 15 years to improve access. But the pharmaceutical industry fights back. PhRMA says the current system is needed to recoup the $2.3 billion average cost of developing a single drug. The debate isn’t over. It’s just getting louder.What This Means for You

If you’re on a brand-name drug, don’t assume it’s safe forever. Check the FDA’s Orange Book. Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic coming?” Most are. If your copay suddenly spikes, it might be because your insurer is waiting for a generic to launch - and they’re holding you to the brand price until then. If you’re on a high-cost drug, consider asking your doctor about switching to a biosimilar or generic when available. You could save thousands. And if you’re waiting for a drug to get cheaper, know this: the clock doesn’t start when it hits shelves. It started when the company filed the patent - often over a decade ago.How long does a drug patent last in the U.S.?

The legal term is 20 years from the patent filing date. But because drug development takes 8-12 years, the actual time a drug is sold without competition is usually 7-12 years. Extensions under the Hatch-Waxman Act can add up to 5 more years, but total market exclusivity can’t exceed 14 years after FDA approval.

Can a drug have more than one patent?

Yes. Most drugs have multiple patents: one for the active ingredient, others for the formulation, manufacturing process, method of use, or delivery system. These secondary patents can extend protection long after the main patent expires, sometimes for decades.

What’s the difference between a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

A patent protects the invention from being copied. Regulatory exclusivity is granted by the FDA and blocks generic companies from even submitting an application for a set time - even if the patent has expired. You can have both at the same time, and they don’t cancel each other out.

Why do some drugs stay expensive even after the patent expires?

Sometimes, insurance plans don’t immediately switch to generics, or they keep high copays during the transition. Also, for biologics, biosimilars take longer to enter the market. And in some cases, companies use legal tactics - like lawsuits or patent thickets - to delay generics, even after the main patent expires.

How can I find out when my drug’s patent expires?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book online. Search by the drug’s brand name. It lists all patents and exclusivity periods. You can also ask your pharmacist or use free tools like DrugPatentWatch or GoodRx, which track expiration dates and generic availability.

Do other countries have the same patent rules?

No. The U.S. uses a 20-year term from filing, but countries like Japan use a different method - calculating from the date of examination request. Some countries allow extensions, others don’t. In the EU, the process is more centralized, and exclusivity periods vary by drug type. This is why a drug might be generic in Canada but still brand-name in the U.S.

12 Comments

Chuck Dickson

Man, I had no idea patents worked like this. I always thought once the 20 years were up, generics just rolled in. Turns out Big Pharma’s been playing 4D chess with our prescriptions this whole time. Thanks for laying this out so clearly - I’m gonna check my meds on the Orange Book tonight.

Robert Cassidy

Of course they do. The system’s rigged. 20 years? More like 20 years of taxpayer-funded R&D, then 15 more years of corporate greed wrapped in legal loopholes. This isn’t innovation - it’s legalized robbery. And don’t get me started on how they outsource manufacturing to China while screaming ‘American jobs!’

Naomi Keyes

Actually, the Hatch-Waxman Act allows for up to five years of patent term extension - but only if the extension period does not cause the total market exclusivity period to exceed fourteen years from the date of FDA approval, and the application for extension must be filed within sixty days of approval - and even then, it’s subject to USPTO review, which can be delayed due to backlog, and the extension is calculated on a case-by-case basis, often requiring detailed documentation of the time lost during clinical trials, which must be verified by the FDA - and many companies miss the deadline, which is why only 60% of drugs actually receive extensions - not all of them, as the article misleadingly implies.

Dayanara Villafuerte

So basically… Big Pharma is like that one friend who brings a whole extra set of chairs to a party just so no one else can sit down 😒💊

Patent thickets? More like legal spiderwebs. And we’re the flies.

Also, if you’re on a $100k drug and your copay jumped from $50 to $200? That’s not a glitch. That’s capitalism with a side of betrayal. 🤡

Andrew Qu

This is one of those posts that feels like a public service. Most people don’t realize how much of their healthcare costs are tied to legal maneuvers, not science. If you’re on a chronic med, take 10 minutes to look up the Orange Book. It’s free. Your wallet will thank you. And if your pharmacist seems annoyed when you ask about generics? Ask again. They’re there to help - even if the system isn’t.

kenneth pillet

orange book is a mess but its free. check it. generics come sooner than you think. just wait.

Jodi Harding

They’re not just extending patents. They’re extending suffering.

Danny Gray

Wait - if the patent clock starts when you file, not when you sell, doesn’t that mean the first person to file a drug idea gets to monopolize it for decades, even if they never actually make it? Sounds less like innovation and more like a legal lottery where the rich buy all the tickets.

Tyler Myers

This is all part of the New World Order. The FDA, USPTO, and Big Pharma are all connected to the same shadowy cabal that controls the money supply. They delay generics so they can inject tracking chips into the pills. You think your copay is high now? Wait till your blood pressure meds start sending location data. They’re already testing it in Canada.

Kristin Dailey

America invented this system. We don’t need WHO telling us how to run our pharma.

Stacey Marsengill

It’s not just expensive - it’s cruel. People are choosing between insulin and rent. And the people who designed this? They’re on a yacht in the Med, laughing. They call it ‘innovation.’ I call it moral bankruptcy.

Aysha Siera

China is behind this. They control the active ingredients. The 20-year patent? A distraction. The real monopoly is in rare earth minerals used in pill coating. They own the supply chain. You think you’re buying medicine? You’re buying Chinese leverage.